Supervised by: Ayesha Aziz

Conducted by: M. Mesum Abbas, M. Shoaib & Hamna Nadeem

Affiliated with: COMSATS University Islamabad, Lahore Campus

In the modern age, media is no longer limited to entertainment it has evolved into one of the most influential forms of storytelling.

Every drama, advertisement, news update, or social media trend subtly shapes our thoughts, emotions, and daily interactions.

Where once classic literature nurtured children’s creativity, today the glowing TV screen has quietly taken its place. As storybooks rest on the shelves, screens have become the new bedtime companions, redefining childhood in ways we seldom notice.

Just like literature, television also tells stories that mirror human experiences. In the past, children explored imaginative worlds through books like Alice in Wonderland or The Secret Garden, where every character and scene existed only through words.

These books helped young readers develop imagination, empathy, and curiosity. Today, television performs a similar function yet with one major difference: it provides ready-made images.

Children no longer need to imagine how a character looks or how a scene unfolds; everything appears visually before them. While this makes storytelling more engaging, it can reduce the depth of imagination and emotional development that reading once encouraged.

News and social media have also become a new kind of “text” for both children and adults. Just as literature once raised awareness through fictional narratives, modern media brings real-life issues directly to the public.

During the floods in Pakistan, TV channels and social platforms showed heartbreaking visuals of affected families, motivating people across the country and even globally to help.

Movements like #JusticeForZainab prove that stories told through headlines, images, and hashtags can awaken moral consciousness, much like powerful literature has done for centuries.

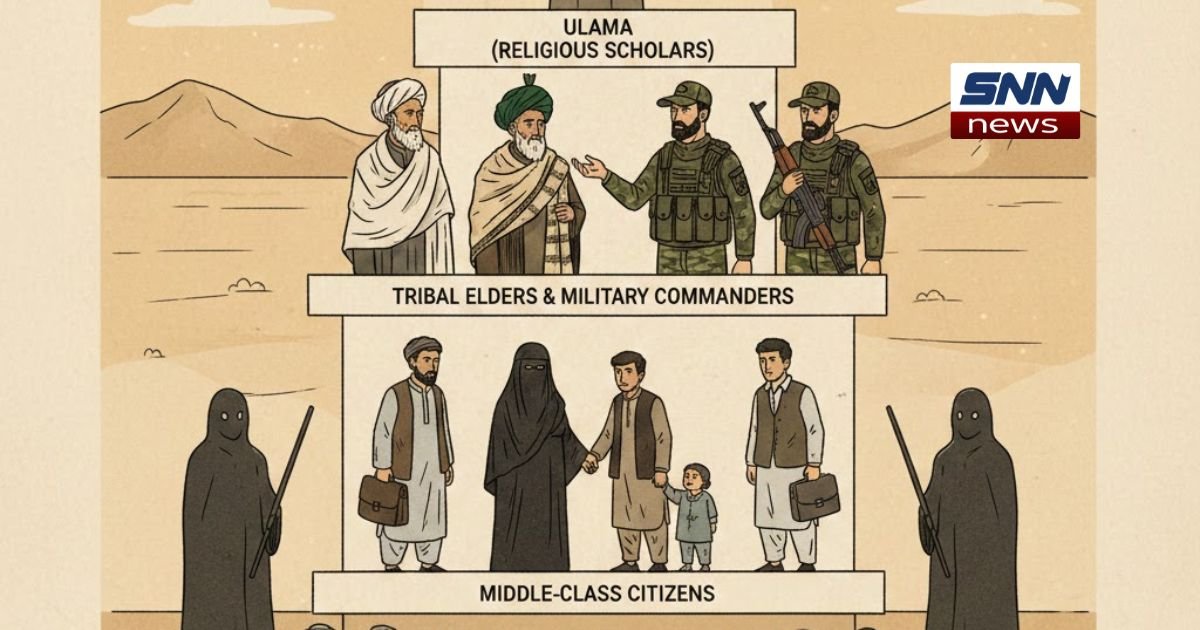

From a literary perspective, this shift shows how storytelling continues to adapt with time. A Marxist critic might argue that television now teaches class values, capitalism, and consumer desires. A feminist critic could examine how women are portrayed in dramas and advertisements.

A reader-response theorist would claim that every viewer interprets a show differently based on their life experiences just as readers interpret novels uniquely.

Ultimately, television has not replaced literature it has simply become its visual evolution. The purpose of media analysis, like literary criticism, is not to reject modern storytelling but to understand it more deeply.

Media has already proven its power to unite communities, raise awareness, and inspire positive change. The real challenge now is for audiences to demand thoughtful,

responsible, and meaningful content stories that build character, broaden perspectives, and spark imagination. When creators and viewers work together, media can become more than just a reflection of society; it can guide us toward a kinder, wiser, and more imaginative future.

Conclusion

In the end, television may be reshaping childhood, but the responsibility still lies with us. If parents, educators, and viewers demand meaningful stories, media can evolve from simple entertainment to a tool that builds imagination, empathy, and critical thinking.

Just as literature once guided young minds, thoughtful visual stories can inspire a new generation one that learns not just from words or screens, but from the values behind them. The future of storytelling depends on the choices we make today.

“Media shapes society, but society must also shape media.”

M. Mesum Abbas, M. Shoaib & Hamna Nadeem

“Read our detailed analysis on how media shapes modern storytelling.”